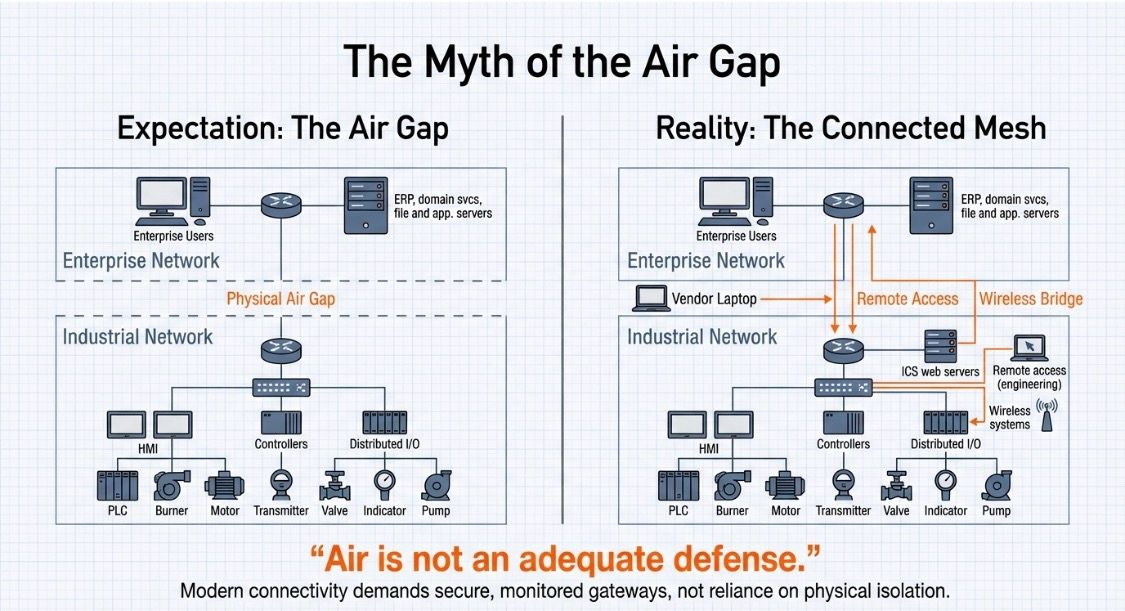

For decades, the concept of the “air gap” stood as an unshakeable pillar of security within Operational Technology (OT) environments. It was the industrial equivalent of a moat around a castle – a physical separation designed to keep hostile forces at bay. Plant managers and engineers often rested easy, convinced that if a Programmable Logic Controller (PLC) wasn’t wired directly to the internet, their facility remained an impenetrable fortress. The simple logic was compelling: if it can’t be reached, it can’t be attacked. This belief, however, has become a dangerous misconception in the modern industrial era.

True air gaps, once considered the gold standard, are now largely extinct. The inexorable march of digital transformation, fueled by the demand for real-time data, predictive maintenance, and remote troubleshooting, has irrevocably punctured this vacuum. The rigid isolation of the past has given way to an interconnected web of systems, creating a complex and often vulnerable landscape. This article will delve into the dissolution of the air gap, explore the realities of IT/OT convergence, identify the evolving tactics of adversaries, and outline the foundational countermeasures essential for securing contemporary industrial operations.

The Dissolution of a Decades-Old Doctrine

The traditional understanding of an air-gapped network was straightforward: absolute physical separation from any other network, especially the internet. This meant no cables, no wireless links, and data transfer strictly limited to manual methods, such as USB drives, often envisioned as a security measure for critical infrastructure like nuclear facilities and military systems. This ideal, however, began to erode significantly in the late 1990s as industrial organizations started integrating their systems with enterprise resource planning (ERP) software. The push for greater efficiency and visibility laid the groundwork for today’s highly interconnected environments.

What replaced the true air gap was not necessarily better security, but often “carefully managed mythology,” as one expert suggests. The dramatic increase in OT-specific monitoring, with SANS Institute’s 2024 survey reporting 52% of organizations adopting it compared to 33% in 2019, underscores this growing interconnectedness. The COVID-19 pandemic further accelerated this trend, with 65% of organizations reporting increased IT and OT network interconnection due to the demands of remote work.

The core reasons for the air gap’s dissolution are multifaceted, driven by both technological advancements and operational necessities.

Industrial Modernization and the Need for Data

Many industrial plants were designed and built before the widespread adoption of the internet, making them “air-gapped by design.” When digital technology eventually entered these environments, it was initially contained. However, initiatives to modernize dated industrial facilities are actively dissolving these old boundaries. Stand-alone equipment, from pumps to valves, is increasingly automated and remotely controlled for enhanced efficiency and effectiveness. Furthermore, modern OT devices are often built on common platforms like Windows and Linux, rather than proprietary and less-known systems, significantly increasing their exposure to cyber threats.

The demand for real-time data is a primary driver of IT/OT convergence. Companies are merging IT with operations to boost efficiency, reduce costs, and gain competitive advantages. Real-time access to operational data facilitates better planning, predictive maintenance, and reduced downtime. This integration allows organizations to revolutionize their operations, improving capabilities and reach, such as the remote control of machine-driven coal refinery trucks, enabling continuous mining operations in remote areas.

The Proliferation of IoT and Shadow IT

The Internet of Things (IoT) has exponentially expanded the attack surface within industrial environments. The introduction of smart devices – from employees’ personal tablets and smartphones to corporate surveillance cameras and building management systems with smart door locks – creates numerous new entry points for potential attackers. These devices, often connecting to both IT and OT networks, can inadvertently bridge the gap that organizations mistakenly believe exists.

Beyond official IoT deployments, the phenomenon of “shadow IT” further complicates the picture. This refers to IT systems and solutions built and used within organizations without explicit organizational approval. In an OT context, this might manifest as unauthorized network connections set up by operational staff for convenience, quick troubleshooting, or to bypass perceived bureaucratic hurdles. These shadow connections, though often well-intentioned, can create unforeseen backdoors and vulnerabilities, allowing attackers to find a logical path from enterprise IT networks down into critical industrial systems like SCADA, DCS, PLCs, pumps, and valves.

The Reality of IT/OT Convergence: An Expanding Attack Surface

The connected mesh of IT/OT convergence is no longer avoidable; it’s an operational imperative. While it delivers undeniable benefits in efficiency, productivity, and informed decision-making, it also dramatically expands the attack surface. The days of distinct, isolated networks are long over, replaced by complex interconnectivity that blurs traditional boundaries.

The Blurring Lines: Interconnected Networks

The integration of IT and OT systems means that threats targeting an organization’s IT infrastructure can now potentially impact its operational processes. For instance, an email phishing attack on an IT employee could, through lateral movement, eventually lead to the compromise of industrial control systems. This interconnectedness is not always a result of deliberate, planned integration. “Accidental convergence” frequently occurs, often due to a lack of careful segmentation, insufficient security controls, or a general unawareness of the shared infrastructure.

This accidental convergence can arise from various scenarios:

- Shared Infrastructure: Common networking components (switches, routers) or even shared servers that inadvertently connect both IT and OT segments.

- Remote Access Solutions: Implementation of remote access for IT personnel or third-party vendors that, without proper isolation and monitoring, can provide an entry point into the OT network.

- Data Historians and MES: Systems like data historians and Manufacturing Execution Systems (MES) inherently bridge the gap, collecting data from OT for analysis and reporting within the IT domain. While crucial for operations, they represent significant conduits for potential threat propagation.

Security researchers leveraging tools like Shodan, a search engine for internet-connected devices, routinely discover industrial control systems exposed directly to the internet. These aren’t the result of sophisticated hacking; they are simply systems visible to anyone with a web browser, a clear indicator that the air gap is a myth for many.

Shadow Connections and Unintentional Backdoors

The most insidious aspect of a dissolved air gap is the proliferation of “shadow currents” or shadow connections. These are often established to bypass perceived security hurdles or as quick fixes, inadvertently creating backdoors that adversaries can exploit.

Common examples include:

- Engineering Workstations: These are perhaps the most common bridge. They reside on OT networks but require regular updates, vendor support, and access to technical documentation, often necessitating connections to IT networks or the internet. A compromised engineering workstation can serve as a direct conduit for malware to propagate into the OT domain.

- USB Drives: The “sneakernet” – the manual transfer of data via USB drives – is a classic vector for bypassing air gaps. Even in highly secure environments, USB drives are used for software updates, configurations, or transferring logs. If an infected USB drive is introduced, it can effortlessly propagate malware into an “isolated” network.

- Vendor Remote Access: Third-party vendors often require remote access for maintenance, troubleshooting, and software updates. While legitimate, if not rigorously controlled and monitored, these connections can be exploited by attackers or inadvertently introduce vulnerabilities.

- Modem Connections: Older industrial sites might still rely on dial-up modems for remote access, which, if exposed, can be a forgotten entryway into the network.

These seemingly innocuous connections, born out of operational necessity or convenience, collectively render the air gap obsolete and provide attackers with ample opportunities to penetrate industrial defenses.

The Evolving Adversary: No Longer Requiring Physical Presence

In the era of the mythical air gap, securing industrial facilities often centered around physical security measures, assuming an attacker would need to be physically present to cause disruption. Today, this assumption is dangerously outdated. Adversaries no longer need to physically enter a facility to cause malfunction; they leverage the dissolved air gap and the interconnectedness of IT and OT to launch sophisticated attacks remotely.

The implications are profound. Cyber threats have evolved to exploit even the most isolated systems, demonstrating that an air gap can provide a misleading sense of security.

Lateral Movement: The Jump from Carpeted to Oily Floor

One of the most critical attack methodologies in an IT/OT converged environment is lateral movement. Attackers seek out connections – literal or logical – that allow them to “jump from the carpeted floor (IT) to the oily floor (OT).” This often involves exploiting established remote access solutions or ICS web servers.

Examples of such lateral movement vectors include:

- Remote Access Gateways: VPNs, jump servers, or other remote access infrastructure intended for legitimate IT or vendor access become prime targets. Once compromised, these gateways can grant attackers direct access to the OT network.

- Shared Management Platforms: Integrated IT/OT management platforms or HMI (Human-Machine Interface) servers connected to both domains can be used as pivot points.

- Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) and Manufacturing Execution Systems (MES): As mentioned, these systems inherently bridge the divide between business and operational processes. A successful breach of the ERP system can provide a pathway to the MES, and subsequently, to the underlying control systems.

- Active Directory Exploitation: Many OT environments rely on Active Directory for authentication, often shared with IT. Compromising Active Directory within IT can provide attackers with credentials valid for accessing OT systems.

Notable incidents like Pipedream/Incontroller (2022) have demonstrated how attackers can effectively “leap over air-gaps” using malicious code, negating the traditional belief in physical isolation as a primary defense.

The Human Pivot: Unintentional Mules for Malware

Even in environments with robust technical controls, the human element remains a significant vulnerability, serving as an unintentional “mule” for malware. This “human pivot” often involves third parties or internal staff who, through no malicious intent, introduce threats into an OT network.

Key scenarios include:

- Third-Party Laptops: Contractors or service technicians bringing their laptops to perform maintenance. These devices may have been connected to untrusted networks or inadvertently infected. When connected directly to the industrial network, they can bypass perimeter firewalls and introduce malware, as exemplified by the Stuxnet attack and its reliance on infected USB drives.

- Mobile Devices and Personal USBs: Employees connecting their personal smartphones, tablets, or USB drives to workstations within the OT network for charging or data transfer can unintentionally introduce malicious code.

- Social Engineering: Phishing attacks targeting OT personnel can trick individuals into executing malicious code or divulging credentials, providing attackers with initial access.

The 2020 Snake/EKANS ransomware, for instance, initially infiltrated IT networks but possessed functionality designed to disable ICS processes. This highlighted its potential ability to cross supposedly air-gapped environments through lateral movement or insider threats, including those facilitated by human error.

Protocol Exploitation: Designed for Reliability, Not Security

A critical vulnerability within many OT environments lies in the very protocols that govern their operations. Industrial control protocols (ICPs) like Modbus, PROFINET, and DNP3 were primarily designed for reliability, real-time performance, and efficiency in environments where security was an afterthought. Consequently, many lack fundamental security features such as encryption, authentication, or integrity checks.

This inherent lack of security makes them ripe for exploitation:

- Lack of Authentication: Attackers can issue commands to PLCs or other controllers without needing to authenticate, allowing them to manipulate processes directly.

- Absence of Encryption: Data transmitted over these protocols is often in plain text, making it susceptible to eavesdropping and manipulation. An attacker can intercept and alter commands or sensor readings.

- Replay Attacks: Without integrity checks, attackers can capture legitimate communication and “replay” it later to trick controllers into performing unauthorized actions.

- Denial of Service (DoS): Exploiting vulnerabilities in protocol implementation can lead to a denial of service, disrupting critical industrial processes.

While modern iterations of these protocols and newer protocols do incorporate security features, a vast installed base of legacy equipment continues to rely on insecure versions, making protocol exploitation a potent attack vector for adversaries who can gain access to the OT network.

The Imperative for Foundational Countermeasures

Given the dissolution of the air gap and the evolving threat landscape, the traditional reliance on physical isolation is no longer an adequate defense. Industrial organizations must adopt a proactive and systematic approach to OT cybersecurity, built upon a set of foundational countermeasures. These measures provide the bedrock upon which more advanced security controls can be built, ensuring a robust defense against modern threats.

1. Inventory: You Can’t Protect What You Can’t See

The first and most fundamental step in securing any environment, especially a complex OT one, is to understand what you have. If you can’t see it, you can’t protect it. A comprehensive and accurate inventory of all assets connected to the OT network is paramount.

This inventory should include:

- Hardware Assets: PLCs, RTUs, DCS components, HMIs, engineering workstations, servers, network devices (switches, routers, firewalls), IoT devices, and even transient assets like maintenance laptops.

- Software Assets: Operating systems, firmware versions, application software, security patches installed, and configurations.

- Network Connections: Mapping all connections within the OT network, to the IT network, and to external entities (e.g., cloud services, third-party vendors).

- Communication Protocols: Identifying all protocols in use, both standard (e.g., TCP/IP) and industrial (e.g., Modbus, EtherNet/IP, PROFINET, DNP3).

How to achieve this:

- Passive Monitoring: Deploying sensors that passively listen to network traffic to identify devices, their communication patterns, and installed software. This is often preferred in OT environments to avoid disrupting critical processes.

- Active Scanning (Controlled): Conducting controlled, network-friendly active scans during maintenance windows or on isolated segments to gather detailed information.

- Manual Inventory: For highly sensitive or truly air-gapped segments (which are rare), manual documentation and verification by operational staff.

- CMDB (Configuration Management Database): Integrating OT asset data into a centralized CMDB for consistent tracking and management.

A detailed and continuously updated inventory provides the necessary visibility to identify vulnerabilities, prioritize security efforts, and detect anomalous behavior.

2. Change Control and Integrity: Distinguishing Normal from Anomalies

In dynamic OT environments, unauthorized or unmanaged changes can introduce significant risks and create opportunities for attackers. Effective change control and integrity monitoring are vital for distinguishing legitimate operational changes from malicious activities.

This involves:

- Baseline Configuration: Establishing a verified baseline configuration for all critical assets (PLCs, controllers, HMIs, network devices).

- Change Management Process: Implementing a rigorous change management process that requires documentation, approval, and testing for all modifications to software, firmware, hardware, or network configurations. This process should apply to both planned and emergency changes.

- Integrity Monitoring: Continuously monitoring the integrity of critical files, configurations, and application code on OT devices. Any deviation from the baseline should trigger an alert for investigation. This includes:

- Firmware Integrity: Ensuring that the firmware on controllers and devices remains uncompromised.

- PLC Logic Integrity: Verifying that PLC logic has not been tampered with.

- Operating System File Integrity: Monitoring critical OS files on engineering workstations and servers.

- Checksums and Hashing: Utilizing cryptographic checksums or hashing algorithms to detect unauthorized modifications to files and configurations.

By meticulously managing and monitoring changes, organizations can quickly identify and respond to deviations, whether they are accidental misconfigurations or indicators of a malicious intrusion.

3. Log Management: Correlate Events Across the Plant

Logs are the digital breadcrumbs of activity within any system, offering invaluable insights into operations, errors, and security incidents. Effective log management involves collecting, aggregating, and analyzing logs from diverse OT sources to correlate events across the entire plant.

Key aspects of robust log management include:

- Centralized Log Collection: Aggregating logs from various OT devices (PLCs, controllers, HMIs, ICS servers, network devices), operating systems (Windows, Linux), and security tools into a central repository, often a Security Information and Event Management (SIEM) system.

- Standardized Logging: Where possible, standardizing log formats to facilitate easier parsing and analysis. Industrial protocols like Syslog can be used to forward logs.

- Time Synchronization: Ensuring all devices in the OT network are synchronized to a common time source (e.g., NTP server) to accurately correlate events across different systems.

- Correlation Rules: Developing correlation rules within the SIEM to identify patterns or sequences of events that indicative of a potential security breach or operational anomaly. For example, multiple failed login attempts followed by a successful login from an unusual IP address.

- Long-Term Storage and Retention: Retaining logs for an appropriate period as required by compliance regulations or for incident investigation and forensic analysis.

- Alerting and Reporting: Configuring alerts for critical events and generating regular reports on security posture, compliance, and operational trends.

Comprehensive log management transforms raw data into actionable intelligence, enabling faster detection and response to cyber threats impacting operational continuity.

4. Vulnerability Management: Prioritizing Risks in OT

Vulnerability management in OT requires a specialized approach, moving beyond generic IT scanning to address the unique characteristics and constraints of industrial environments. It’s not just about identifying vulnerabilities but also about prioritizing remediation based on operational risk and managing legacy systems that cannot be easily patched.

Essential practices for OT vulnerability management:

- OT-Specific Scanners: Utilizing vulnerability scanners designed for OT networks that understand industrial protocols and device types, and are less likely to disrupt sensitive operations. Passive monitoring is often preferred here.

- Contextual Risk Assessment: Prioritizing vulnerabilities not just by their technical severity (e.g., CVSS score) but by their potential impact on operational safety, reliability, and business continuity. A vulnerability in a critical control system might be a higher priority than an equally severe one in a non-essential HMI.

- Vendor Advisories and Intelligence: Staying up-to-date with vendor advisories, ICS-CERT alerts, and threat intelligence specifically related to OT components.

- Patch Management Strategy: Developing a carefully planned and tested patch management strategy. Patches must be thoroughly tested in a non-production environment before deployment to ensure compatibility and prevent operational disruptions.

- Isolation for Unpatchable Systems: Identifying legacy systems that cannot be patched (e.g., older Windows XP machines still critical to operations) and implementing compensating controls such as network isolation, micro-segmentation, and rigorous access controls to protect them. This reduces their exposure to known vulnerabilities.

- Regular Audits and Assessments: Conducting periodic security audits, penetration tests (in controlled environments), and configuration reviews to identify weaknesses.

Effective vulnerability management reduces the attack surface and minimizes the potential impact of exploits, even against systems that cannot be fully secured.

5. Segmentation: Eliminating the Flat Network

The “flat network” – where IT and OT systems reside on the same broadcast domain with minimal internal separation – is an adversary’s dream. It allows for effortless lateral movement once initial access is gained. Network segmentation is a crucial countermeasure, replacing the mythical single air gap with a series of smaller, more manageable security zones.

This involves:

- Zone and Conduit Model (Purdue Model): Implementing a layered defense strategy, often based on the Purdue Enterprise Reference Architecture model, which divides industrial environments into distinct zones (e.g., enterprise IT, DMZ, manufacturing operations, control systems, basic control).

- Secure Conduits with Industrial-Aware Firewalls: Establishing secure communication pathways (conduits) between these zones using industrial-grade firewalls. These firewalls are specifically designed to understand and inspect industrial protocols, providing deep packet inspection (DPI) to enforce granular access controls based on the semantics of OT traffic.

- Micro-segmentation: Further subdividing larger zones into smaller, isolated segments. For example, isolating specific PLCs or groups of machines from others, limiting communication to only what is absolutely necessary.

- VLANs and ACLs: Utilizing Virtual Local Area Networks (VLANs) and Access Control Lists (ACLs) to logically separate traffic and restrict communication between different device types or functional groups.

- Unidirectional Gateways (Data Diodes): For highly critical and sensitive data flows from OT to IT, unidirectional security gateways (data diodes) can be employed. These hardware-enforced solutions allow data to flow only in one direction, preventing any return path for malicious traffic.

- Zero Trust Principles: Applying Zero Trust principles, where no device or user is inherently trusted, regardless of its location within the network. All access requests are continuously verified.

By breaking down the flat network into secure, segmented zones, organizations can significantly limit the blast radius of an attack, making it much harder for adversaries to move laterally and impact critical operations.

Moving Beyond Foundational: Functional and Advanced Controls

Establishing the foundational countermeasures (Inventory, Change Control & Integrity, Log Management, Vulnerability Management, and Segmentation) provides a robust platform for OT cybersecurity. However, security is not a static state; it’s an ongoing journey. Once these foundations are solidified, organizations can progressively implement more sophisticated functional and advanced controls.

These next steps often include:

- Advanced Threat Detection: Implementing intrusion detection/prevention systems (IDS/IPS) specifically tuned for OT environments, behavior anomaly detection, and security analytics.

- Secure Remote Access: Deploying highly secured and monitored remote access solutions for vendors and internal staff, incorporating multi-factor authentication (MFA) and least privilege principles.

- Identity and Access Management (IAM): Strengthening user and machine identity controls, ensuring that only authorized individuals and devices can access specific resources, and enforcing role-based access control (RBAC).

- Security Awareness Training: Regularly educating OT personnel about cybersecurity threats, best practices, and their role in maintaining a secure environment.

- Incident Response Planning: Developing and regularly testing an OT-specific incident response plan to ensure a swift and effective reaction to cyberattacks.

- Data Backups and Recovery: Implementing robust backup and disaster recovery strategies for critical OT data and configurations.

- Supply Chain Security: Extending security considerations to the OT supply chain, ensuring that hardware and software components from vendors are secure.

Conclusion: Embracing the Connected Reality

The myth of the air gap in OT security is a dangerous one, offering a false sense of security in an increasingly interconnected world. The forces of industrial modernization, the insatiable demand for real-time data, and the pervasive influence of IT/OT convergence have dismantled the physical isolation that once defined industrial security. Adversaries are no longer confined to physical entry points; they exploit the very connectivity that drives modern industrial efficiency through lateral movement, human vulnerabilities, and the inherent weaknesses of legacy OT protocols.

To survive and thrive in this new reality, organizations must abandon the illusion of the air gap and wholeheartedly embrace a proactive cybersecurity posture. This begins with the foundational countermeasures: meticulously inventorying assets, implementing stringent change control, centralizing log management, executing intelligent vulnerability management, and robustly segmenting networks. These steps are not mere suggestions; they are the essential building blocks for creating a resilient and defensible industrial environment.

The future of OT security is not about retreating to an imagined past of isolation, but about intelligently managing the inherent risks of a connected present and future. By systematically applying these foundational principles, industrial organizations can transform their vulnerabilities into strengths, ensuring operational continuity, safety, and reliability in the face of evolving cyber threats.

Is your industrial operation grappling with the complexities of IT/OT convergence? Do you need expert guidance to solidify your foundational cybersecurity countermeasures and navigate the modern threat landscape?

IoT Worlds offers specialized consultancy services to help industrial organizations build resilient and secure operational environments. From comprehensive asset inventory and vulnerability assessments to designing and implementing robust segmentation strategies, our experts are equipped to guide you through every step of this critical journey.

Don’t let the myth of the air gap expose your most critical assets. Take action today to secure your industrial future.

To learn how IoT Worlds can empower your OT security, send an email to info@iotworlds.com and our team will be in touch to discuss your specific needs.