Humanoid robots are finally stepping out of the lab and into real deployments. Logistics hubs test humanoids in warehouses; factories explore them as flexible co‑workers; research labs around the world use them to push the limits of reinforcement learning and control.

If you work in IoT, robotics, or AI, you face a key question:

Which humanoid platform should I choose, and how does it compare to the alternatives?

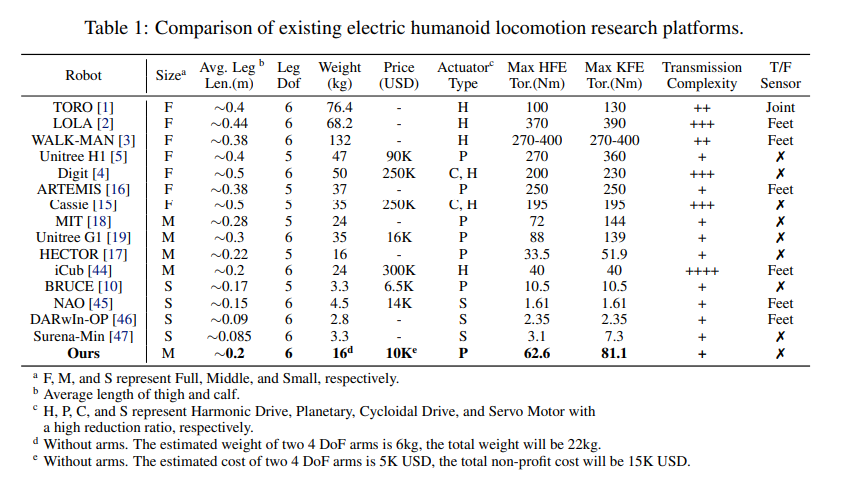

1. Reading the Comparison Table: Columns That Matter

“Ours” corresponds to Berkeley Humanoid.

Let’s start by unpacking the columns in the table. Understanding these terms is vital before you compare numbers.

The table columns are:

- Robot

- Size (F, M, S)

- Average Leg Length (m)

- Leg Degrees of Freedom (DoF)

- Weight (kg)

- Price (USD)

- Actuator Type (H, P, C, S)

- Max HFE Torque (Nm)

- Max KFE Torque (Nm)

- Transmission Complexity (+ to ++++)

- T/F Sensor (Joint / Feet / ✗)

Let’s clarify each.

1.1 Size: Full, Middle, Small

The Size column uses:

F– Full‑size humanoids, roughly adult human dimensions.M– Middle‑size humanoids, about half to three‑quarters human height.S– Small‑size humanoids, often under 0.6m tall.

Size influences:

- how human‑like the robot’s workspace is,

- how dangerous a fall can be,

- how much torque and battery capacity are required,

- and where you can legally or safely test the robot.

Full‑size robots are best for tasks that must closely match human reach (e.g., warehouse shelving designed for people). Middle‑size platforms like the Berkeley Humanoid are ideal for research because they are large enough to exhibit realistic dynamics yet light enough to survive frequent experiments and falls.

1.2 Average Leg Length

The Average Leg Length column approximates the mean of thigh and calf lengths in meters.

Why it matters:

- Longer legs enable longer step lengths and higher theoretical walking speeds.

- But for a given actuator strength, longer legs also mean higher torques are required to lift and move the mass.

Robots in the table have leg lengths around 0.15–0.5m. Full‑size platforms tend toward the upper end; mid‑ and small‑scale designs use shorter limbs to keep torques and costs manageable.

1.3 Leg Degrees of Freedom (DoF)

Each DoF is a joint that provides independent motion (e.g., hip pitch, hip roll, hip yaw).

Common patterns in the table:

- Many full‑ and mid‑size robots use 6 DoF per leg (3 at the hip, 1 at the knee, 2 at the ankle).

- Some designs save cost or weight by reducing ankle or hip DoF.

More DoF means:

- richer motion capabilities (side stepping, turning in place, terrain adaptation),

- but also more actuators, sensors, control complexity, and cost.

The Berkeley Humanoid provides 6 DoF per leg, offering full 3D placement of each foot—a must for dynamic locomotion and rough‑terrain research.

1.4 Weight

Total robot weight, usually including legs and torso; some entries exclude arms and note this in the footnotes.

Weight interacts with:

- safety (a 70kg robot falling over is scary),

- feasible environments (light robots can operate on office floors; heavy ones may require special surfaces),

- power consumption and actuator sizing.

In the table:

- full‑size research platforms like TORO or WALK‑MAN weigh 60–80kg,

- mid‑scale robots including the Berkeley Humanoid cluster around 15–35kg,

- small robots like NAO come in under 6kg.

1.5 Price

Where available, price is listed in USD (one entry uses 10K€, which still represents roughly a low‑five‑figure cost).

Take these as ballpark estimates:

- Some robots are one‑off research prototypes with no commercial price.

- Commercial systems like Digit and Unitree H1 typically sell in the six‑figure range when you include support contracts.

- The Berkeley Humanoid targets approximately 10K€ bill of materials in a non‑profit context—significantly lower than most full‑size machines.

For researchers and IoT startups, price dictates:

- how many robots you can buy,

- whether destructive testing is acceptable,

- and how accessible the platform is to students and smaller labs.

1.6 Actuator Type

The Actuator Type codes:

H– Harmonic drive actuatorsP– Planetary gearbox actuatorsC– Cycloidal drive actuatorsS– High‑reduction servo motors

Each technology has trade‑offs:

- Harmonic drives: high precision and low backlash, but expensive and somewhat fragile.

- Planetary gearboxes: strong and relatively compact; a good all‑round choice for mid‑scale robots.

- Cycloidal gears: excellent shock resistance and high torque capacity; more complex to machine, but now often 3D‑printed in low‑cost designs.

- Servos: cheap, compact, and easy to control, but limited in torque and often with more backlash.

Berkeley Humanoid uses planetary gear actuators—a deliberate compromise between cost, robustness, and performance.

1.7 Max HFE Torque and Max KFE Torque

These two columns list the maximum torque (in Newton‑meters) at:

- HFE (Hip Flexion/Extension) – think of swinging the leg forward and backward.

- KFE (Knee Flexion/Extension) – bending or straightening the knee.

Higher maximum torques enable:

- stronger push‑off during walking and running,

- better recovery from disturbances,

- the ability to handle heavier payloads or rough terrain.

In the table:

- top‑end full‑size robots reach 200–400Nm at the hip and knee,

- mid‑scale designs including Berkeley Humanoid sit in the 60–200Nm range,

- small educational robots often have under 15Nm.

The Berkeley Humanoid achieves about 62.6Nm hip torque and 81.1Nm knee torque, impressive numbers considering its moderate weight and cost.

1.8 Transmission Complexity

A qualitative rating:

+– simple transmission++– moderate+++– complex++++– very complex

High complexity might indicate:

- external belts and linkages,

- multiple stages of gears,

- or non‑trivial placement of motors and joints.

Complex transmissions can be efficient and high‑performance, but:

- they are harder to manufacture,

- require more maintenance,

- and are more fragile when you experiment with aggressive behaviors (e.g., reinforcement learning that still “figures it out” and falls a lot).

Berkeley Humanoid is rated +, reflecting its straightforward, integrated actuator design—good news for maintainability and for labs with limited mechanical resources.

1.9 T/F Sensor Placement

The final column identifies where Torque/Force (T/F) sensors are located:

Joint– direct joint torque sensorsFeet– force sensors under the feet✗– no dedicated T/F sensing

T/F sensors are vital for:

- precise force control and compliant interaction,

- balancing on uneven terrain,

- estimating external disturbances for push recovery.

Some robots, like high‑end iCub, feature joint torque sensors at many joints. Others, including many research humanoids, rely on foot force sensors and inertial measurements to simplify hardware while still enabling balance control.

2. The Robots in the Table: Who’s Who?

Armed with column definitions, let’s briefly walk through the robots listed.

2.1 TORO, LOLA, WALK‑MAN – Early European Full‑Size Platforms

- TORO – a full‑size humanoid from DLR (German Aerospace Center). Heavy (≈76kg) with harmonic drives and moderate torque.

- LOLA – from TU Munich, known for precise dynamic walking research. Slightly lighter than TORO, still full‑size and harmonic‑drive based.

- WALK‑MAN – from the Italian Institute of Technology, aimed at disaster‑response scenarios; heavy, powerful, and complex.

These robots blazed the trail for compliant, torque‑controlled humanoids but at a high cost and complexity. They remain excellent lab platforms but are out of reach for most IoT‑focused projects.

2.2 Unitree H1 and Digit – Commercial Full‑Size Humanoids

- Unitree H1 – a full‑height, 47kg humanoid with powerful electric actuators, listed at roughly 90K USD in the table. It uses planetary gearboxes and delivers up to 270Nm hip and 360Nm knee torque. H1 targets general‑purpose tasks and is aggressively marketed as a high‑performance yet comparatively affordable system.

- Digit – Agility Robotics’ commercial humanoid for warehouse logistics. Listed price is around 250K USD. It combines cycloidal and harmonic drives, has strong torso and leg actuation, and includes arms for box handling and other manipulation tasks.

Both H1 and Digit are pushing into real industrial trials. For organizations that need turn‑key platforms with vendor support, these two are leading choices—but their cost and closed nature limit their appeal for deep control research or educational use.

2.3 ARTEMIS and Cassie – Dynamic Locomotion Specialists

- ARTEMIS – a full‑size humanoid with custom force‑controlled electric “muscle” actuators and sophisticated foot sensors. It’s famous for agile walking and running, particularly on rough terrain.

- Cassie – a mid‑scale, bird‑like biped without an upper body, created by the same team that later commercialized Digit. Cassie is widely used as a research platform for reinforcement‑learning‑based locomotion.

These robots show what’s possible when you optimize a design almost exclusively for dynamic legs, rather than for arms or manipulation.

2.4 MIT, Unitree G1, HECTOR, iCub – Advanced Mid‑Scale Humanoids

- MIT Humanoid – a mid‑size robot with a focus on agile locomotion and reinforcement learning. It strikes a balance between power and simplicity.

- Unitree G1 – a mid‑scale commercial humanoid, more affordable than H1 and oriented toward education and research, with about 16K USD price in the table.

- HECTOR – a German research platform with extensive sensor suites.

- iCub – an Italian open‑source humanoid used heavily in developmental and cognitive robotics; it offers rich joint torque sensing and high transmission complexity.

These platforms are excellent for whole‑body control, manipulation, and interaction studies, but their combination of complexity and cost often keeps them in well‑funded labs.

2.5 BRUCE, NAO, DARwIn‑OP, Surena‑Min – Small Humanoids

- BRUCE – a small yet relatively powerful robot for locomotion research, around 6.5kg.

- NAO – a famous educational robot used in thousands of schools and RoboCup competitions worldwide, roughly 14K USD.

- DARwIn‑OP – another widely used small humanoid, from ROBOTIS, excellent for learning basic biped robotics and vision.

- Surena‑Min – a small Iranian research platform with servo‑based actuation.

These robots are ideal for education and early prototyping, but their limited torque and small size make them less suitable for high‑performance locomotion research or realistic industrial tasks.

2.6 Berkeley Humanoid

- Size: Middle

- Avg. leg length: about 0.2–0.3m

- Leg DoF: 6

- Weight: ≈16kg (excluding optional arms)

- Price: 10K€ estimated bill of materials

- Actuator: P (planetary gearboxes)

- Max HFE torque: 62.6Nm

- Max KFE torque: 81.1Nm

- Transmission complexity:

+ - T/F Sensors: Feet

These figures tell a compelling story: a relatively low‑cost, mid‑scale humanoid with serious torque and simple mechanics—a near‑ideal combination for reinforcement‑learning and rough‑terrain research.

We’ll examine Berkeley Humanoid in detail next.

3. Deep Dive: Berkeley Humanoid

3.1 Design Goals

The Berkeley Humanoid project set out with several clear objectives:

- Create a robust, mid‑scale humanoid optimized for learning‑based control.

The robot should tolerate falls, handle uneven terrain, and make it easy to test new locomotion and balance algorithms. - Keep the platform affordable.

A target bill of materials around 10K€ makes it possible for labs and even startups to own multiple units. - Simplify manufacturing and maintenance.

Despite strong torque numbers, the chassis and actuators should use off‑the‑shelf components where possible, with a clean, easily serviceable design. - Ensure strong sim‑to‑real fidelity.

Modeling the robot accurately in simulators like NVIDIA Isaac Gym / Isaac Lab should be straightforward, enabling reinforcement learning policies trained in simulation to transfer reliably to hardware.

In many ways, Berkeley Humanoid was crafted specifically to hit the sweet spot of the comparison table: high enough performance to be meaningful, low enough cost and complexity to be widely accessible.

3.2 Mechanics and Actuators

Each leg of Berkeley Humanoid has:

- 3 DoF at the hip (pitch, roll, yaw),

- 1 DoF at the knee (pitch),

- 2 DoF at the ankle (pitch, roll).

The actuators:

- are based on planetary gearboxes with brushless DC motors,

- deliver peak torques over 60Nm (hip) and 80Nm (knee),

- are compact, allowing tight integration at or near joint axes.

Transmission design favors:

- low backlash for precise control,

- robustness against impacts,

- minimal external belts or linkages, resulting in a

+complexity rating in the table.

This mechanical simplicity is a major advantage when the robot is used for reinforcement learning: students and researchers can iterate on controllers without spending half their time repairing fragile hardware.

3.3 Sensors and Electronics

Berkeley Humanoid employs:

- joint encoders for precise angle measurement,

- foot force sensors for ground reaction forces,

- an IMU for attitude and acceleration,

- standard embedded controllers and a primary onboard computer for high‑level planning and learning‑based controllers.

Because the platform is targeted at autonomy and RL, the computing stack is built to support:

- low‑level PID or torque control loops,

- higher‑level neural network policies executing at 100–500 Hz,

- logging of telemetry for offline analysis and further training.

3.4 Control and Locomotion Results

The UC Berkeley team demonstrated several behaviors on this platform:

- Stable, long‑distance walking on varied terrain, including sidewalks and indoor surfaces.

- Trail hiking and steep incline walking, showing the robot can manage real outdoor environments.

- Single‑ and double‑leg hopping, something only a handful of humanoids have achieved.

- Push‑recovery behaviors, where the robot resists or recovers from significant external forces.

Importantly, many of these behaviors were generated using reinforcement learning policies trained in simulation, then transferred to the real robot with minimal tuning—a hallmark of good robot design for AI research.

4. Why a Mid‑Scale, Affordable Humanoid Matters

With high‑profile full‑size robots like Tesla Optimus, Figure 01, Digit, and Unitree H1 in the news, one might ask:

Why should we care about a mid‑size platform like Berkeley Humanoid, instead of going straight to full human scale?

There are several practical reasons.

4.1 Safety and Risk

A 70kg full‑size robot falling over is both dangerous and expensive.

That risk limits:

- how aggressively you can explore new control algorithms,

- where you can operate (safety certifications, insurance, physical environment),

- who can interact with the robot (only trained personnel).

At 16kg, Berkeley Humanoid is still heavy enough to behave like a serious biped, but:

- injuries from falls are far less likely,

- damage to floors and fixtures is minimal,

- and undergrads or hobbyists can operate the robot after reasonable training.

4.2 Research Throughput

Because the hardware cost is relatively low, a lab can afford multiple units. That unlocks:

- parallel experiments,

- A/B testing of different controllers,

- redundancy when one unit needs repair.

With one ultra‑expensive full‑size robot, downtime is crippling. With three or four mid‑scale robots, your team can keep pushing forward.

4.3 Sim‑to‑Real Efficiency

Modeling a mid‑scale robot accurately is easier than a full‑scale one:

- dynamic effects like structural flexing and cable compliance are less extreme,

- actuator models are conceptually simpler,

- contact forces are smaller, leading to gentler discontinuities.

All of this makes physics simulation more stable and faithful, which directly benefits reinforcement learning.

4.4 Accessibility and Education

For the IoT and AIoT ecosystem to flourish, a broad base of developers and engineers must have hands‑on access to humanoid hardware.

A 10K€ platform like Berkeley Humanoid—or an even cheaper derivative like Berkeley Humanoid Lite—lays the foundation for:

- university courses on embodied AI,

- hackathons and innovation competitions,

- startups experimenting with new business models around humanoid services.

5. Extending the Family: Berkeley Humanoid Lite

The comparison table focuses on traditional metal‑and‑gearbox humanoids, including Berkeley Humanoid. Since then, the same group has introduced Berkeley Humanoid Lite, an ultra‑low‑cost, 3D‑printed version designed for maximum accessibility.

Key features of Berkeley Humanoid Lite:

- Sub‑$5{,}000 USD hardware cost using 3D‑printed cycloidal gearboxes and off‑the‑shelf motors.

- Approximately 16kg weight, similar to the original.

- Full 6‑DoF legs and multi‑DoF arms, enabling walking and manipulation.

- Fully open‑source CAD files, firmware, and control software.

While Lite is not explicitly in the original table, you can think of it as a “younger sibling” to Berkeley Humanoid:

- smaller budget,

- slightly lower torque and robustness,

- but even more accessible and highly modifiable.

For IoTWorlds readers, Lite is especially interesting as a bridge between robotics and IoT maker culture. It is the kind of platform that could live in a university fab lab or innovation garage, connected to cloud IoT services and experimented with by many teams.

6. Benchmarking Berkeley Humanoid Against the Table

Let’s synthesize the table’s data into a few key comparisons.

6.1 Torque vs. Weight

A useful rough metric is torque‑to‑weight ratio at major joints.

- Full‑size robots like Unitree H1 and Digit have high absolute torque but also high weight.

- Small robots like NAO have modest torque and low weight.

Berkeley Humanoid’s ≈62.6Nm hip and 81.1Nm knee torque for a 16kg robot translates to very strong relative capabilities. It can:

- perform dynamic movements (hopping, fast stepping),

- handle slopes and obstacles,

- carry modest payloads without stalling.

6.2 Cost vs. Performance

Another comparison is cost vs. locomotion capability.

- Digit and H1 cost many times more than Berkeley Humanoid but add manipulation and full human scale.

- Small educational robots are cheaper but cannot replicate human‑like dynamics.

Berkeley Humanoid sits in a sweet zone:

- far more powerful and anthropomorphic than NAO or DARwIn‑OP,

- but an order of magnitude more affordable than industrial humanoids.

For research groups focused on locomotion, control, and AI, that cost‑to‑capability ratio is tough to beat.

6.3 Complexity vs. Maintainability

Finally, transmission complexity:

- iCub, with

++++, offers beautiful but intricate torque‑sensing mechanics—fantastic for detailed studies, but challenging to maintain. - Berkeley Humanoid’s

+rating indicates a simpler transmission that is easier to assemble, inspect, and repair.

When experimenting with new, possibly unstable algorithms, this simplification pays off in less downtime and shorter repair cycles.

7. Humanoid Robots as IoT and AIoT Devices

Humanoids are not just mechanical marvels—they are also intelligent, networked devices. Let’s connect the table’s hardware focus with the IoTWorlds perspective.

7.1 Sensing and Data Streams

Most robots in the table, including Berkeley Humanoid, provide rich sensor streams:

- joint positions and velocities,

- ground reaction forces,

- IMU data (orientation and acceleration),

- sometimes cameras, depth sensors, or LiDAR.

In an IoT system, these data become:

- inputs to cloud‑based analytics or digital twins,

- health and diagnostics information for predictive maintenance,

- sources of behavioral insights (e.g., how often a robot interacts with particular zones or objects).

7.2 Edge AI and Connectivity

Berkeley Humanoid and similar platforms typically embed:

- an onboard computer (often x86 or ARM) running Linux or a real‑time OS,

- networking interfaces (Ethernet, Wi‑Fi, or 5G modems),

- GPUs or NPUs for vision and learning inference in more advanced configurations.

This allows multiple deployment patterns:

- Fully local control, with all computation done on the robot, ideal for areas with poor connectivity or tight latency constraints.

- Edge‑cloud hybrid, where high‑level planning, learning, or map building happens in the cloud, while low‑level control remains on‑board.

- Swarm or fleet management, where many humanoids share information via a central IoT platform and coordinate tasks.

7.3 Integration With Industrial IoT Platforms

In factories or warehouses, humanoids must integrate with:

- MES and WMS systems (Manufacturing Execution, Warehouse Management),

- SCADA or building‑management systems,

- safety PLCs and human‑presence detection systems.

Open platforms like Berkeley Humanoid make it easier to run:

- ROS 2 nodes that communicate via MQTT or OPC UA,

- custom IoT dashboards and APIs,

- AI pipelines that combine robot telemetry with other plant sensors.

This is where IoTWorlds readers can contribute the most: designing the data architectures and applications that turn locomotion capability into business value.

8. How to Choose a Humanoid Platform for Your Project

Given the comparison table and the deep dive above, how should you pick a robot for your needs?

8.1 For Academic Research in Locomotion and RL

Priorities:

- strong legs,

- good sim‑to‑real models,

- fall tolerance,

- and an open or at least modifiable control stack.

Berkeley Humanoid and Cassie are prime choices here. Berkeley Humanoid adds arms and a more human‑like body; Cassie specializes purely in legs.

8.2 For Industrial Pilots and Proofs of Concept

Priorities:

- vendor support,

- safety certification,

- manipulators that can interact with existing tools.

Platforms like Digit and Unitree H1 may be more appropriate, despite their high cost, because they come as supported products with roadmaps.

Berkeley Humanoid can still play a role as an internal testbed where your team refines behaviors and integration strategies before committing to large‑scale commercial deployments.

8.3 For Education and Maker Communities

Priorities:

- low cost,

- ease of assembly and repair,

- strong community and documentation.

Small robots like NAO and DARwIn‑OP still have a place, but for more advanced curricula and maker spaces, Berkeley Humanoid Lite offers a unique combination of:

- affordability (sub‑$5K),

- serious walking and manipulation capabilities,

- open‑source design that students can modify and extend.

8.4 For AIoT Startups

If you are building a startup around:

- autonomous inspection and maintenance,

- humanoid‑as‑a‑service,

- or smart environment interaction,

you may want:

- one or two commercial humanoids to impress customers and run early pilots, and

- several mid‑scale research platforms like Berkeley Humanoid to develop algorithms, interfaces, and connectivity stacks in a more cost‑effective sandbox.

9. Future Outlook: Toward a Humanoid IoT Ecosystem

As we move toward a world of AI‑enabled factories, smart buildings, and connected infrastructure, humanoid robots will evolve from isolated experiments to integral IoT nodes.

9.1 Standardized APIs and Data Models

We can expect:

- ROS 2 and similar frameworks to converge on standard message types for humanoid kinematics, forces, and tasks.

- Cloud IoT platforms to offer native integrations for popular humanoids, with pre‑built dashboards and analytics.

- Digital twin software to support importing URDF/SDF models for robots like Berkeley Humanoid and to simulate them alongside production lines and logistics flows.

9.2 AI‑Native Connectivity (5G/6G)

As 5G Advanced and eventually 6G roll out, humanoids will benefit from:

- ultra‑low‑latency wireless control and teleoperation,

- AI‑native RAN features that prioritize robot traffic for safety,

- integrated localization and sensing at the radio level.

Mid‑scale, widely available platforms like Berkeley Humanoid make perfect testbeds for these next‑generation networks.

9.3 Democratized Embodied AI

Open designs such as Berkeley Humanoid Lite suggest a future where:

- high schools host humanoid robotics clubs,

- community labs experiment with humanoid art installations,

- local startups prototype services—delivery, elder care, facility monitoring—without needing $1M budgets.

The comparison table that began this article may someday look quaint, a snapshot from a time when only a few dozen labs owned humanoids. But understanding it today helps us navigate the transition from rare, bespoke platforms to a rich ecosystem of interconnected, intelligent humanoid IoT devices.

10. Key Takeaways

- The comparison table lists 16 electric humanoid locomotion platforms and compares them on size, weight, torque, actuator type, cost, and complexity.

- Berkeley Humanoid is a mid‑scale, 16kg robot with 6‑DoF legs, planetary actuators, ≈62.6Nm hip and 81.1Nm knee torque, simple transmissions, foot force sensors, and a bill‑of‑materials cost around 10K€.

- This design hits a sweet spot: powerful enough for dynamic outdoor locomotion and learning‑based control, yet affordable and robust enough for widespread research use.

- Platforms like Digit and Unitree H1 dominate full‑scale commercial trials but are much more expensive and often closed. Small robots like NAO and DARwIn‑OP are great for early education but lack realistic dynamics.

- Berkeley Humanoid Lite extends accessibility further, offering a 3D‑printed, open‑source humanoid for under $5{,}000, suitable for education, makers, and IoT experimentation.

- For IoT and AIoT, humanoids act as mobile edge‑AI devices: they sense, compute, and act, and must integrate with networks, clouds, and digital twins.

- Choosing the right platform depends on your goals—research, industrial pilots, education, or startups—but understanding the table’s metrics ensures you pick on capability and value, not hype.

Humanoid robotics is no longer a niche; it is becoming a central pillar of the intelligent, connected world. The Berkeley Humanoid platforms show that you don’t need a mega‑budget to join the movement. You just need the right balance of performance, cost, and openness.