Embedded systems are the silent workhorses behind the Internet of Things (IoT), powering everything from smart home devices to industrial automation. At the heart of every embedded system lies the ability to communicate, both internally between components and externally with other devices and networks. The sophistication and efficiency of these communication channels dictate an IoT system’s overall performance, reliability, and functionality.

This article delves into the diverse world of communication channels used in embedded systems, categorizing them into two primary types: wired and wireless. We will explore the unique characteristics, applications, and advantages of various protocols within each category, providing a comprehensive understanding for anyone looking to design, implement, or simply comprehend IoT solutions.

The Essence of Embedded System Communication

Before diving into specific protocols, it’s crucial to understand why communication is so fundamental to embedded systems, especially in the context of IoT. Embedded systems are typically designed to perform dedicated functions. To achieve these functions and interact with the wider world, they need to:

- Exchange data with sensors and actuators: Gathering environmental data or controlling physical mechanisms.

- Interface with other microcontrollers or processors: Distributing tasks and consolidating information.

- Connect to external networks or the cloud: For data storage, analysis, remote control, and user interaction.

The choice of communication channel heavily influences factors such as data transfer speed, power consumption, range, reliability, security, and cost. A well-chosen communication protocol ensures seamless operation, enabling the true potential of IoT applications.

Key Factors Influencing Protocol Selection

When selecting a communication protocol for an embedded system, several critical factors must be considered:

- Data Rate: How much data needs to be transferred and how quickly? High-bandwidth applications like video streaming require different protocols than simple sensor readings.

- Distance: How far apart are the communicating devices? Short-range wireless might suffice for a smart home, while long-range cellular is essential for remote asset tracking.

- Power Consumption: How critical is battery life? Low-power protocols are vital for battery-operated devices, whereas always-on devices might tolerate higher consumption.

- Reliability and Error Handling: How crucial is data integrity? Industrial applications often demand highly reliable protocols with robust error detection and correction.

- Cost: What is the budget for hardware components and implementation? Some protocols require more expensive transceivers or more complex wiring.

- Security: What level of data protection is required? Sensitive data necessitates protocols with strong encryption and authentication mechanisms.

- Topology: How are the devices connected? Point-to-point, multi-drop, or mesh network topologies influence protocol choice.

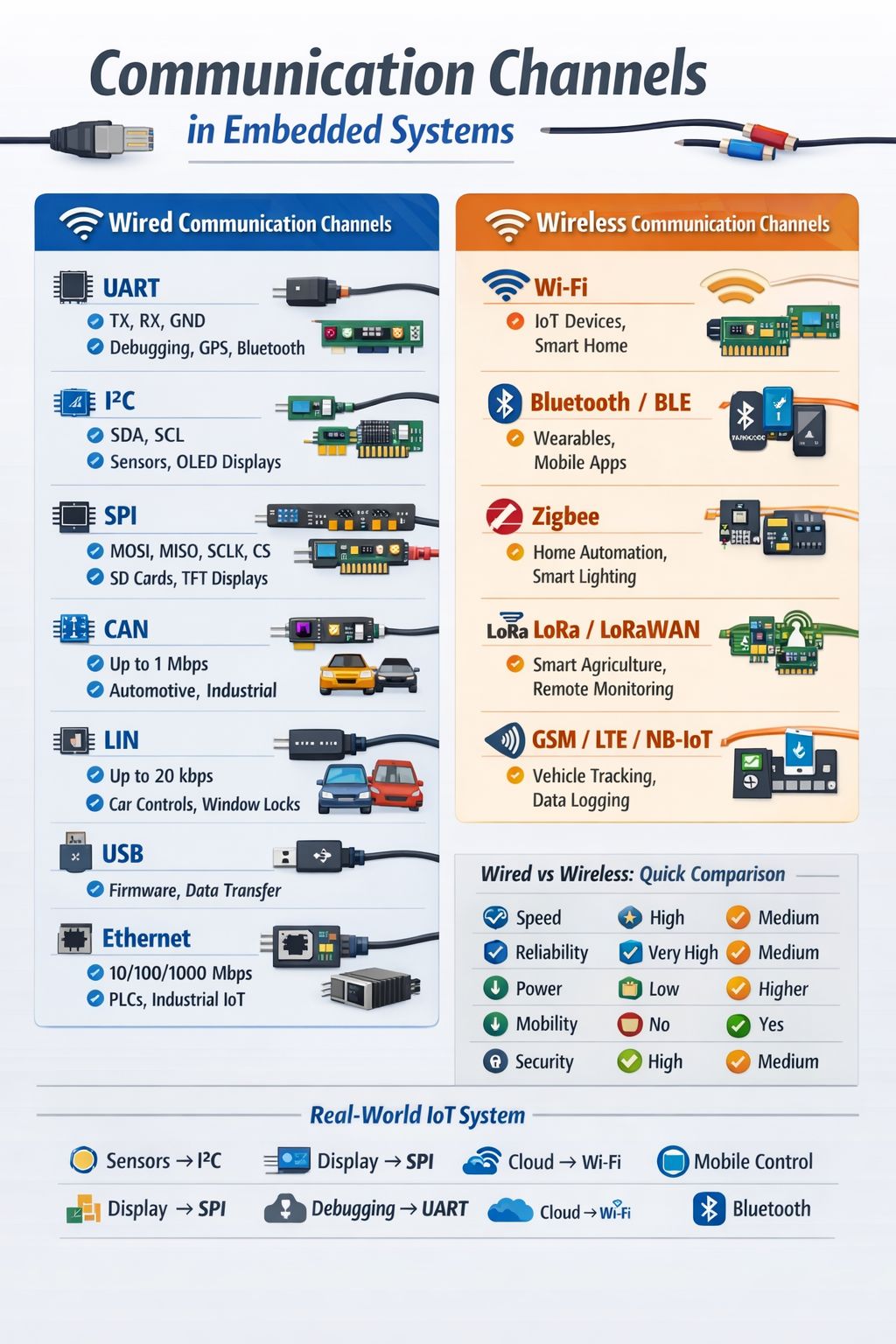

Wired Communication Channels: The Backbone of Stability

Wired communication channels rely on physical cables to transmit data, offering inherent advantages in terms of reliability, speed, and security. While they might lack the mobility of wireless solutions, their steadfast performance makes them indispensable for many embedded system applications.

UART (Universal Asynchronous Receiver Transmitter)

UART is one of the oldest and most fundamental serial communication protocols. It facilitates asynchronous serial data transmission between two devices, typically microcontrollers or between a microcontroller and a peripheral.

Operational Overview

UART operates with two data lines: TX (transmit) and RX (receive), along with a common GND (ground) reference. “Asynchronous” means there’s no shared clock signal between the sender and receiver. Instead, both devices must agree on a baud rate (bits per second) for communication. Data is transmitted byte by byte, prefixed by a start bit and suffixed by stop bits, providing synchronization for each byte.

Key Characteristics

- Type: Serial, Asynchronous

- Wires:

TX,RX,GND - Speed: Low to Medium

- Applications: Debugging outputs to a console, interfacing with GPS modules for location data, communicating with Bluetooth modules (like HC-05) for wireless connectivity to other devices.

- Advantages: Simple to implement, low cost, widely available in microcontrollers for point-to-point communication.

I²C (Inter-Integrated Circuit)

I²C, pronounced “eye-squared-see,” is a synchronous, multi-master, multi-slave serial bus developed by Philips. It’s highly popular for connecting various peripheral integrated circuits (ICs) over short distances.

Operational Overview

I²C uses two bidirectional open-drain lines: SDA (Serial Data Line) for data transfer and SCL (Serial Clock Line) for clock synchronization. Both lines are pulled high with resistors. The master device initiates communication, controls the clock, and addresses specific slave devices using a unique 7-bit or 10-bit address. This addressing scheme allows multiple devices to share the same two wires.

Key Characteristics

- Type: Serial, Synchronous, Multi-master

- Wires:

SDA,SCL - Speed: Standard mode up to 100 kbps, Fast mode up to 400 kbps, Fast-mode Plus up to 1 Mbps, and Ultra-Fast mode up to 5 Mbps [totalphase.com].

- Applications: Reading data from various sensors (temperature, pressure, accelerometers), controlling Real-Time Clocks (RTC), and driving OLED displays.

- Advantages: Requires only two wires for multiple devices, supports multiple masters, and is widely supported by a vast array of ICs.

SPI (Serial Peripheral Interface)

SPI is another synchronous serial communication interface specification used for short-distance communication, primarily in embedded systems. It’s often favored for its higher data transfer rates compared to I²C.

Operational Overview

SPI typically operates in a master-slave configuration and uses four wires: MOSI (Master Out Slave In), MISO (Master In Slave Out), SCLK (Serial Clock), and CS (Chip Select) or SS (Slave Select). The master generates the clock signal (SCLK) and controls the CS line to select the target slave device. Data can be transmitted and received simultaneously (full-duplex operation).

Key Characteristics

- Type: Serial, Synchronous

- Wires:

MOSI,MISO,SCLK,CS - Speed: Very High (MHz range), making it significantly faster than I²C or UART [totalphase.com].

- Applications: Interfacing with SD cards for data storage, driving TFT (Thin-Film Transistor) displays for graphics, and communicating with Flash memory chips for persistent storage.

- Advantages: Fast data transfer rates, full-duplex communication, and simpler hardware implementation compared to I²C (no unique addressing scheme required for slaves, as

CShandles selection).

CAN (Controller Area Network)

CAN is a robust vehicle bus standard designed to allow microcontrollers and devices to communicate with each other in applications without a host computer. It’s particularly prevalent in the automotive sector.

Operational Overview

CAN is a multi-master serial bus that uses a differential pair of wires (CAN_H and CAN_L) for communication, providing high noise immunity. Messages are broadcast to all nodes on the network, but only the intended recipient processes the message based on its identifier. It employs a sophisticated error detection and fault confinement mechanism, making it highly reliable. Data rates can range up to 1 Mbps.

Key Characteristics

- Type: Serial, Multi-master

- Speed: Up to 1 Mbps

- Applications: Automotive systems (engine control units, airbags, ABS), industrial automation for factory floor communication, and embedded control systems requiring high reliability.

- Advantages: Highly reliable and error-resistant, multi-master capabilities, excellent electromagnetic compatibility (EMC), and robust to noise.

LIN (Local Interconnect Network)

LIN is a cost-effective serial communication protocol often used as an alternative to CAN in automotive applications where bandwidth and versatility are not as critical.

Operational Overview

LIN is a single-master, multiple-slave serial communication protocol that operates using a single wire plus ground (or sometimes two wires for enhanced reliability). It’s designed for low-cost, low-speed communication between smart sensors and actuators. Baud rates are typically much lower than CAN, up to 20 kbps.

Key Characteristics

- Type: Serial, Low speed, Single-master

- Speed: Up to 20 kbps

- Applications: Car door locks, window control systems, climate control components, and other non-critical automotive functions.

- Advantages: Low cost, simple implementation, and reduced wiring harness complexity compared to CAN.

USB (Universal Serial Bus)

USB is a widely adopted standard for connecting peripheral devices to a host computer. While primarily designed for computer peripherals, its versatility has extended its use into embedded systems for various purposes.

Operational Overview

USB supports various data rates (from low-speed 1.5 Mbps to SuperSpeed+ 20 Gbps) and power delivery capabilities. It operates in a master-slave configuration, with the host acting as the master. It handles power management, device discovery, and configuration automatically.

Key Characteristics

- Speed: High (various specifications available)

- Applications: Firmware updates for embedded devices, high-speed data transfer to and from external memory or computers, and debugging embedded systems via a virtual serial port.

- Advantages: Universal adoption, hot-swappable devices, power delivery over the data cable, and a well-defined standard ensuring interoperability.

Ethernet

Ethernet is a family of wired computer networking technologies widely used in local area networks (LANs) and metropolitan area networks (MANs). It provides high-speed, reliable communication across larger distances than other wired embedded protocols.

Operational Overview

Ethernet operates at the data link layer and physical layer of the OSI model, defining specifications for cabling, connectors, and communication protocols. It uses a variety of speeds (10 Mbps, 100 Mbps, 1 Gbps, 10 Gbps, and beyond) and employs different cabling types (e.g., twisted pair, fiber optic). In IoT, it typically uses the TCP/IP suite for network-level communication.

Key Characteristics

- Type: Network communication

- Speed: 10/100/1000 Mbps and higher

- Applications: Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs) in industrial settings, robust Industrial IoT (IIoT) deployments requiring deterministic communication, and connecting high-bandwidth networking devices.

- Advantages: Very high data rates, reliable over longer distances, standard for network connectivity, robust error handling, and widely supported infrastructure.

Wireless Communication Channels: The Freedom of Connectivity

Wireless communication channels transmit data without physical wires, using radio waves, infrared, or other forms of electromagnetic radiation. They offer unparalleled mobility and ease of deployment, crucial for many IoT applications, albeit sometimes at the expense of power consumption or bandwidth.

Wi-Fi

Wi-Fi refers to a family of wireless networking protocols based on the IEEE 802.11 standards. It’s synonymous with local area wireless connectivity and internet access.

Operational Overview

Wi-Fi operates primarily in the 2.4 GHz and 5 GHz ISM (Industrial, Scientific, and Medical) radio bands. It enables devices to connect to a local network and, through a router, to the internet. Wi-Fi offers high data rates, making it suitable for applications requiring significant bandwidth. However, this comes with a higher power consumption compared to some other wireless protocols.

Key Characteristics

- Range: Medium (typically tens of meters indoors, hundreds outdoors)

- Speed: Very High (tens to hundreds of Mbps)

- Applications: Connecting standard IoT devices like smart cameras, smart home systems, and cloud connectivity for data upload and remote control.

- Advantages: High data rates, widespread adoption, existing infrastructure (routers), and comprehensive networking capabilities.

- Disadvantages: Higher power consumption makes it less ideal for battery-powered, long-lived devices without frequent recharging [expertbeacon.com].

Bluetooth / BLE (Bluetooth Low Energy)

Bluetooth is a short-range wireless technology standard for exchanging data between fixed and mobile devices, and building personal area networks (PANs). Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) is a power-optimized variant.

Operational Overview

Both Bluetooth and BLE operate in the 2.4 GHz ISM band. Standard Bluetooth (Classic Bluetooth) is designed for continuous, higher data rate connections (e.g., audio streaming). BLE, introduced in Bluetooth 4.0, is optimized for very low power consumption, making it ideal for sporadic data transfers and battery-constrained devices. Devices can communicate directly with each other or with a smartphone/tablet.

Key Characteristics

- Range: Short (typically up to 10-100 meters, depending on class)

- Power: Low (BLE is extremely power-efficient) [expertbeacon.com]

- Applications: Wearables (fitness trackers, smartwatches), mobile apps for device control and data logging, smart devices (sensors, smart locks, beacons), and health monitoring systems.

- Advantages: Very low power consumption (BLE), direct device-to-device communication, widespread support in smartphones, and relatively low cost.

Zigbee

Zigbee is a low-power, low-data-rate, short-range wireless mesh networking standard based on the IEEE 802.15.4 specification. It’s designed for simple, inexpensive devices that require long battery life.

Operational Overview

Zigbee operates in the 2.4 GHz ISM band (globally) and other regional bands. Its key feature is its mesh networking capability, where devices can relay data for other devices, extending the network’s effective range and improving reliability. It’s often used in conjunction with a gateway that bridges the Zigbee network to Wi-Fi or Ethernet for internet connectivity.

Key Characteristics

- Range: Medium (tens of meters, extended by mesh networking)

- Power: Very Low

- Applications: Home automation (smart thermostats, security sensors), smart lighting systems, and industrial monitoring where mesh capabilities are beneficial.

- Advantages: Very low power consumption, self-healing mesh networking, high scalability, and relatively low cost per node.

LoRa / LoRaWAN

LoRa (Long Range) is a proprietary physical layer modulation technique, while LoRaWAN (Long Range Wide Area Network) is the open standard network protocol that uses the LoRa modulation. It’s designed for long-range, low-power, low-data-rate IoT applications.

Operational Overview

LoRaWAN operates in license-free sub-GHz radio frequency bands (e.g., 868 MHz in Europe, 915 MHz in North America). It supports very long communication ranges (several kilometers) at the expense of data rate. A single LoRaWAN gateway can handle thousands of end-devices, making it suitable for large-scale deployments.

Key Characteristics

- Range: Very Long (several kilometers in rural areas, up to a few kilometers in urban environments) [expertbeacon.com]

- Speed: Low (tens of bps to tens of kbps)

- Applications: Smart agriculture (soil moisture sensors, livestock tracking), smart cities (parking sensors, waste management), remote monitoring of utilities (water meters, gas meters), and environmental sensing.

- Advantages: Extremely long range, very low power consumption (multi-year battery life), high capacity (many devices per gateway), and robust against interference.

GSM / LTE / NB-IoT (Cellular Technologies)

These are cellular communication technologies that leverage existing mobile phone network infrastructure to connect IoT devices. They offer very long range and established global coverage.

Operational Overview

- GSM (Global System for Mobile Communications): A 2G technology still used for basic, low-data-rate IoT applications, particularly for SMS and small data packets.

- LTE (Long Term Evolution): A 4G technology offering high data rates, suitable for more demanding IoT applications like video streaming or complex data uploads.

- NB-IoT (Narrowband IoT): A Low-Power Wide-Area Network (LPWAN) technology based on LTE, specifically designed for low-power, low-data-rate, long-range IoT devices. It excels in deep indoor penetration and massive device connectivity.

- LTE-M (Long Term Evolution for Machines): Another LPWAN technology optimized for IoT, offering higher bandwidth than NB-IoT and supporting voice capabilities, suitable for applications like asset tracking that might require occasional voice interaction or firmware over-the-air updates.

Key Characteristics

- Range: Very Long (global coverage where cellular networks exist) [expertbeacon.com]

- Applications: Vehicle tracking, remote data logging from industrial equipment or environmental sensors, smart metering, and critical infrastructure monitoring.

- Advantages: Ubiquitous coverage, high reliability, strong security measures inherent in cellular networks, and suitability for mobile IoT applications.

- Disadvantages: Higher power consumption (especially GSM/LTE), ongoing subscription costs for cellular data plans.

Wired vs. Wireless: A Quick Comparison

The decision between wired and wireless communication is often a trade-off based on project requirements. Here’s a brief comparative overview:

| Feature | Wired Communication | Wireless Communication |

|---|---|---|

| Speed | High | Medium (can be higher for Wi-Fi) |

| Reliability | Very High | Medium |

| Power | Low | Higher (can be very low for BLE/LoRaWAN/NB-IoT/Zigbee) |

| Mobility | No | Yes |

| Security | High | Medium |

Speed: Wired connections generally offer higher and more stable data rates. While Wi-Fi can be very fast, its speed can fluctuate with signal strength and interference.

Reliability: Wired connections typically provide superior reliability due to their immunity to electromagnetic interference and physical obstructions. Wireless can be subject to signal loss, fading, and interference.

Power: Wired connections often consume less power from the embedded device itself (power might be supplied over the cable). Wireless communication, especially high-bandwidth solutions, can be power-intensive, a critical factor for battery-operated IoT devices. However, protocols like BLE, LoRaWAN, and NB-IoT are specifically designed for ultra-low power operation.

Mobility: This is where wireless truly shines. Devices can be placed and moved freely without the constraint of physical cables.

Security: Wired connections are generally considered more secure as physical access is required to tap into the network. Wireless security relies on robust encryption and authentication protocols, which, if improperly implemented, can be vulnerable.

Real-World IoT System: A Blend of Communication Channels

A typical, complex IoT system rarely relies on a single communication protocol. Instead, it leverages a combination of wired and wireless channels, each chosen for its suitability to a specific task or segment of the system. Let’s consider a practical example as illustrated below.

Example IoT System Walkthrough

Imagine a smart environmental monitoring system deployed in a remote agricultural setting. This system aims to collect various environmental parameters, display some information locally, allow for remote control via a mobile app, and upload data to a cloud platform for analysis.

- Sensors to Microcontroller (

I²C):- Multiple environmental sensors (temperature, humidity, soil moisture) are connected to a central microcontroller.

I²Cis an excellent choice here. Its two-wire bus allows multiple sensors to be easily integrated without excessive wiring, and their data rates are low, perfectly handled byI²C‘s synchronous communication. Each sensor would have a uniqueI²Caddress.

- Display to Microcontroller (

SPI):- A small TFT display is used to show real-time sensor readings locally on the device.

SPIis preferred for displays due to its higher data transfer speed. This allows for faster screen updates and more fluid graphical interfaces, enhancing the user experience.

- Debugging Output (

UART):- During development and for on-site diagnostics, engineers need to monitor the system’s internal state or print error messages.

UARTprovides a simple, low-cost serial port for debugging. AUART-to-USB converter can connect the system to a laptop for live console output.

- Local Control and Data Access (

Bluetooth):- A farmer wants to quickly check current conditions or adjust a setting via their smartphone without internet access.

Bluetooth(specifically BLE for low power) allows the microcontroller to communicate directly with a mobile application on the farmer’s phone, providing local control and data synchronization.

- Cloud Connectivity (

Wi-FiorLoRaWAN, orCellular):- For long-term data storage, trend analysis, and remote monitoring from anywhere, the data needs to be sent to a cloud platform.

- If a local internet connection is available (e.g., a Wi-Fi hotspot at the farm),

Wi-Fiis an ideal choice due to its high bandwidth and established internet protocols. - However, if internet infrastructure is sparse,

LoRaWANmight be chosen for its long-range capabilities to connect to a nearby gateway, then upstream to the internet. - For truly remote locations without any local network,

GSM/LTE/NB-IoTcould be used, leveraging cellular networks to send data directly to the cloud.

This example highlights how different communication channels are intelligently combined to build a robust and versatile IoT solution, optimizing for factors like proximity, data rate, power efficiency, and connectivity availability.

The Future of IoT Communication

The landscape of IoT communication is continuously evolving. We see increasing demand for:

- Lower power consumption: Extending battery life for truly autonomous devices.

- Enhanced security: Protecting sensitive data from cyber threats.

- Greater interoperability: Devices from different manufacturers seamlessly communicating.

- Edge computing capabilities: Processing data closer to the source to reduce latency and bandwidth usage.

- AI/ML integration: Smart communication protocols that adapt to network conditions and data patterns.

New protocols and enhancements to existing ones are constantly emerging to meet these demands, pushing the boundaries of what IoT can achieve. Understanding the foundational communication channels discussed here is the first step toward navigating this exciting and complex future.

Accelerate Your IoT Vision with Expert Guidance

Navigating the intricate world of IoT communication channels and embedded systems can be a daunting task. Whether you’re conceptualizing a new smart product, optimizing an existing IoT solution, or seeking to integrate complex communication protocols, expert guidance can be invaluable.

At IoT Worlds, we specialize in transforming innovative ideas into functional, efficient, and secure IoT deployments. Our team brings deep expertise in selecting the right communication technologies, designing robust embedded systems, and building scalable cloud architectures. From initial feasibility studies and proof-of-concept development to full-scale deployment and ongoing support, we partner with you at every stage of your IoT journey.

Don’t let the complexities of IoT communication limit your innovation. Reach out to us today to discuss your project and discover how IoT Worlds can help you achieve your goals.

Contact us for a tailored consultation: