A bastion host is a hardened, tightly controlled entry point placed at a network boundary (often in a DMZ) to provide controlled administrative access into a protected network. A jump host (or jump box/jump server) is the intermediate system you “jump through” to reach internal targets—often used for RDP/SSH pivoting and to centralize logging, access control, and tooling. In practice, many organizations use the terms interchangeably, but a good rule is: “bastion” describes a security-hardened boundary role, while “jump host” describes the operational access pattern (multi-hop). The safest designs combine both: a hardened bastion/jump host in a DMZ plus strict least-privilege access to specific targets.

Why this confusion matters (and how it causes real breaches)

“Jump host vs bastion” sounds like semantics—until it isn’t.

In real environments, teams use the words loosely and end up building access paths that are:

- Too open (a “jump box” that’s basically a shared admin workstation)

- Too trusted (one host becomes a single point of compromise into everything)

- Poorly observed (no session logging, no command auditing, no accountability)

- Operationally brittle (admins bypass it because it’s slow, unstable, or annoying)

The result is predictable: when attackers gain credentials or remote access tooling (phishing, vendor compromise, password reuse), a poorly designed jump/bastion pattern turns into an easy pivot point—especially into high-value targets like domain controllers, hypervisors, backup systems, or OT engineering workstations.

If you’re designing secure remote access, you don’t just need the right name. You need the right role, placement, and control set.

Definitions: jump host vs bastion host

What is a bastion host?

A bastion host is a server designed to be a highly hardened entry point into a protected network segment. Key traits:

- Positioned at a boundary (commonly a DMZ, or a restricted management subnet)

- Exposed (directly or indirectly) to less trusted networks

- Built to minimize attack surface (limited services, strict firewalling, strong auth)

- Often used as the only allowed administrative ingress to internal systems

Mental model: a heavily fortified guard tower at the edge of the castle.

What is a jump host?

A jump host is an intermediate system you use to hop from one network zone to another—commonly to reach systems not directly reachable from your origin network. Key traits:

- Used for multi-hop access (example: laptop → jump host → server/PLC management interface)

- Often concentrates admin tools (RDP client, SSH client, browser, vendor tooling)

- Can be in a DMZ, management subnet, or internal admin zone

- Its big value is controlled pivoting + centralized logs + reduced direct exposure

Mental model: a controlled stepping stone that prevents direct traversal.

Are they the same thing? The honest answer

In many organizations, “bastion host” and “jump host” refer to the same box: a hardened server you must access first before reaching anything sensitive.

But conceptually:

- “Bastion” describes the security posture and boundary function.

- “Jump” describes the access workflow (a hop/pivot).

So you can have:

- A bastion host that is not used for jumping (rare, but possible—e.g., it’s the only place you administer devices from, and devices don’t allow inbound from anywhere else).

- A jump host that is not a bastion (common in bad designs—e.g., a convenient shared workstation with weak hardening).

The best practice is to design a host that is both:

- Bastion-like (hardened boundary entry point), and

- Jump-like (the enforced hop for administrative sessions).

Key differences (quick comparison table)

| Category | Bastion host | Jump host |

|---|---|---|

| Primary meaning | Security-hardened boundary entry point | Intermediate hop to reach internal targets |

| Core objective | Reduce attack surface + enforce strong access control at the edge | Control traversal between zones and centralize admin access |

| Typical location | DMZ / boundary subnet / dedicated management zone | DMZ, management subnet, or internal admin zone |

| Typical protocols | SSH, RDP, sometimes HTTPS to management portals | SSH/RDP to the jump; then SSH/RDP/management tools onward |

| Security posture | Minimal services, strict inbound/outbound rules | Varies (should be hardened, but often isn’t in practice) |

| Logging expectations | High—auth logs, session logs, changes | High—sessions, commands, lateral connections |

| Biggest risk if compromised | Becomes a trusted foothold at the boundary | Becomes a pivot point deeper into the environment |

| Best fit | Controlled ingress across trust boundary | Enforced multi-hop access and segmentation |

Common synonyms and what people really mean

You’ll hear these terms used interchangeably:

- Jump box / jump server: almost always means “RDP/SSH into this first.”

- Bastion: often means “DMZ entry point,” especially in cloud.

- Admin box: can be a jump host, but frequently implies “tooling workstation” (dangerous if unmanaged).

- Privileged Access Workstation (PAW): a hardened admin endpoint; not necessarily a jump/bastion, but often paired with one.

- Gateway server: may mean remote access termination or protocol gateway.

- RDP gateway: a specific Microsoft role; can be part of a bastion/jump design.

Tip for clarity: In your documentation, define the role explicitly:

- “Access Gateway (Bastion) in DMZ”

- “Jump Host for multi-hop RDP/SSH into management network”

- “PAW for admin endpoint hardening”

Where each one belongs in a network (IT, cloud, and OT/ICS)

Traditional IT (data center / enterprise)

Common placement patterns:

- Bastion in a DMZ or restricted “admin ingress” subnet

- Jump host in an admin/management network that has controlled reach to servers

- Users authenticate from corporate network or VPN into the bastion/jump

Typical reasons:

- Reduce direct inbound exposure to servers

- Centralize control and monitoring

- Enforce MFA and just-in-time privilege

Cloud (AWS/Azure/GCP-style thinking)

Cloud teams often use “bastion” as the standard term.

Patterns include:

- A bastion VM in a public subnet with strict inbound rules (less preferred today)

- A private bastion accessed via VPN/Zero Trust access (more preferred)

- Managed bastion services or session managers that avoid inbound ports entirely

The conceptual role is the same: controlled administrative ingress.

OT/ICS (industrial networks)

OT introduces unique constraints:

- Availability and safety priorities

- Legacy endpoints that can’t run agents

- Vendor tooling that expects “flat” access

- Strict change control and limited maintenance windows

In OT, the safest placement is typically:

- Bastion/jump host in the OT DMZ

- Another controlled hop into OT zones if needed (sometimes a second jump host deeper inside)

The goal is to prevent:

- direct vendor-to-control-zone access

- uncontrolled pivoting from IT to OT

- “dual-homed” shortcuts that bypass firewall policy

Reference architectures

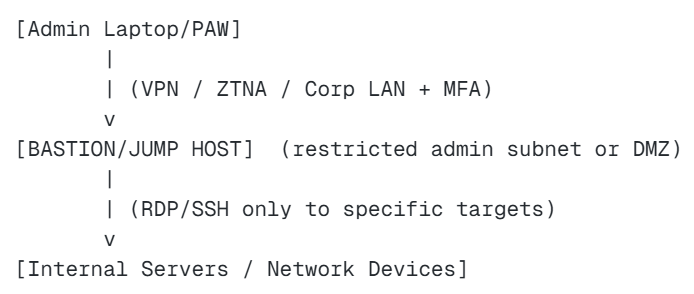

Architecture A: Simple enterprise pattern (one hop)

What this achieves: No direct inbound admin traffic to internal targets from user endpoints.

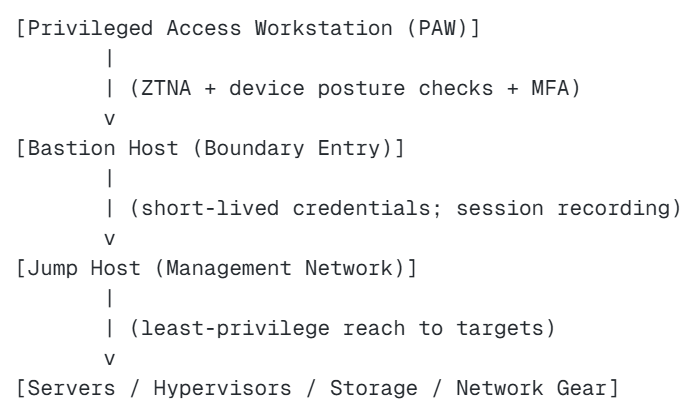

Architecture B: Stronger pattern (PAW + bastion separation)

What this achieves: Reduced exposure and separation of duties. Compromise of one layer doesn’t automatically imply full reach.

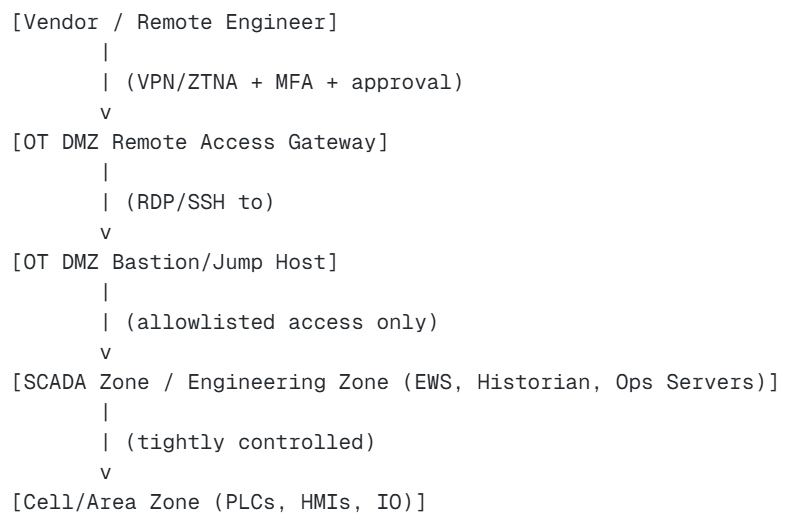

Architecture C: OT pattern (vendor access through OT DMZ)

What this achieves: Vendors do not land directly in control zones. All access is brokered, logged, and restrictable.

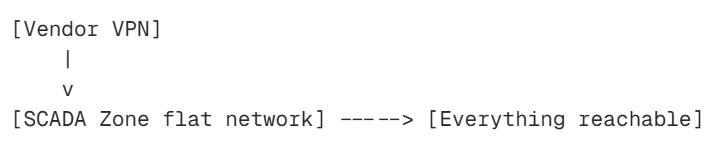

Architecture D: “Don’t do this” (the classic anti-pattern)

Why it fails: One credential compromise becomes plant-wide compromise.

Security controls that make a bastion/jump host actually safe

Whether you call it a bastion or a jump host, the control set matters more than the name. A secure design typically includes:

1) Strong identity controls

- MFA for all interactive logins

- Named accounts (no shared “vendoradmin”)

- Just-in-time access approvals for privileged sessions

- Separate admin accounts from day-to-day accounts

2) Least privilege network reach

- The jump host should only be able to reach what it must manage

- Deny-by-default outbound rules; allowlist protocols and destinations

- Separate admin access by role (network, Windows, OT engineering)

3) Hardening + reduced attack surface

- Minimal installed software (especially browsers/plugins)

- Disable unused services and ports

- Regular patching and configuration management

- Application allowlisting (when feasible)

4) Monitoring, logging, and accountability

- Session recording for high-risk access (vendors, domain admin)

- Command logging (at least for critical admin actions)

- Central log forwarding to SIEM

- Alerts for anomalous access (odd hours, new source IPs, repeated failures)

5) Safe operational workflow

- Make the secure path the easiest path

- Provide tooling required for admins/vendors so they don’t bypass controls

- Build runbooks and support processes so the system isn’t “in the way”

Hardening checklist (Windows RDP + Linux SSH)

Below are pragmatic checklists. Adapt to your environment and risk level.

Windows jump host hardening (RDP-heavy environments)

Baseline controls

- Use a hardened OS build and secure baseline

- Disable unnecessary roles/features (don’t let it become a general-purpose server)

- Restrict local admin membership tightly

- Enforce MFA via your identity provider / privileged access solution

- Use Network Level Authentication (NLA) for RDP

RDP security

- Restrict inbound RDP to known source networks (or ZTNA)

- Limit clipboard/drive redirection where possible (data exfil risk)

- Consider restricting copy/paste for vendor sessions (balance usability)

- Enforce idle timeouts and session lock

Application control

- Install only required admin tools

- Consider application allowlisting to reduce malware execution risk

- Block consumer remote tools (unauthorized TeamViewer/AnyDesk, etc.)

Credential hygiene

- Use separate privileged accounts

- Prevent credential caching where possible

- Avoid storing admin passwords on the host

- Use credential vaulting if available

Logging

- Enable detailed log auditing (auth events, privilege use)

- Forward logs to a central collector

- Monitor for new service installs, scheduled tasks, and persistence attempts

Linux bastion hardening (SSH-heavy environments)

SSH configuration

- Disable password authentication (prefer keys + MFA via SSO/PAM where possible)

- Disable root login over SSH

- Use modern ciphers and key exchange algorithms (per your org policy)

- Rate-limit and protect against brute force (firewall rules, fail2ban-style controls where appropriate)

System hardening

- Minimal packages, remove compilers and unnecessary tools

- Secure file permissions (especially for authorized keys)

- Separate admin duties; use

sudowith least privilege - Keep the host patched and monitored

Network restrictions

- Limit inbound SSH to known IPs or ZTNA

- Restrict outbound connectivity from the bastion (allowlist targets and ports)

Session controls

- Use short session timeouts

- Consider session recording for privileged actions (tooling dependent)

Logging

- Centralize logs, monitor authentication anomalies

- Alert on new users, changes to SSH configs, privilege escalations

Authentication & authorization patterns (MFA, PAM, JIT)

If you’re deciding between “a simple jump box” and a “real bastion,” the difference is usually your identity and privilege model.

Pattern 1: MFA + named accounts (minimum acceptable)

- Every user has a unique identity

- MFA is required

- Access to targets is restricted by group membership

Pros: Simple.

Cons: Privileges can still be “always on.”

Pattern 2: Just-in-time (JIT) privileged access (stronger)

- Users request privileged access for a time window

- Approval workflow exists (human or policy-based)

- Privileged group membership is temporary

Pros: Reduces standing privilege risk.

Cons: Requires process maturity and tooling.

Pattern 3: Credential vaulting + session proxy (very strong)

- Users never see target passwords/keys

- Bastion proxies sessions to targets

- Sessions can be recorded and controlled

Pros: Excellent accountability and control.

Cons: More complex, often needs PAM tooling.

Practical recommendation: For high-risk environments (OT, critical infrastructure, regulated industries), aim for JIT + session logging/recording for vendor and admin access. For smaller environments, start with MFA + strict allowlists + strong logging, then mature.

Logging & session recording: what to capture and why

A jump/bastion host is your best chance to create high-quality audit evidence. But only if you capture the right telemetry.

Log categories you should collect

- Authentication events: successful logons, failures, MFA events, source IP/device info

- Session events: session start/stop, duration, target systems accessed

- Privilege events: elevation actions (admin group use,

sudo, privileged token use) - Configuration changes: firewall rules, user/group changes, scheduled tasks/services

- File transfer events: uploads/downloads if your tool supports it

What “good” looks like operationally

- You can answer: “Who accessed OT engineering workstation X on Tuesday at 2:13 AM, from where, and what did they do?”

- You can quickly distinguish routine maintenance from suspicious behavior.

- Your logs are forwarded off-host, protected from tampering, and retained per policy.

Session recording: where it’s most valuable

- Vendor access into OT

- Domain admin sessions

- Changes to firewall rules and remote access policies

- Access to backup systems and hypervisors

Recording isn’t always mandatory, but when it’s feasible, it’s a powerful control for both investigation and deterrence.

OT/ICS focus: jump host vs bastion in the OT DMZ

OT environments magnify the consequences of poor access design. A compromise can mean production loss, safety risk, environmental events, and long recovery times.

Why OT DMZ placement is the dominant pattern

Placing the bastion/jump host in the OT DMZ helps you:

- terminate remote access before it reaches control zones

- inspect, monitor, and restrict traffic crossing the boundary

- enforce least privilege conduits to SCADA/engineering zones

- reduce the likelihood of “direct-to-PLC” remote sessions

A useful OT rule of thumb

If a remote user (employee or vendor) can reach:

- PLCs,

- safety systems,

- or engineering workstations

…without passing through a controlled, logged jump/bastion workflow, your risk is unnecessarily high.

Do you ever need more than one jump host in OT?

Sometimes, yes—especially in large plants:

- DMZ bastion/jump for remote ingress and session control

- Inner jump host in a restricted engineering/admin zone for tighter separation

- Separate access paths for vendors vs internal engineers

This supports segmentation and reduces the blast radius if one zone is compromised.

Vendor remote access: the pattern that passes audits

Regardless of which standard you align to (IEC 62443 concepts, NIST guidance, internal policy), auditors and risk owners tend to look for the same outcomes:

- No shared vendor accounts

- MFA enforced

- Access is approved and time-bound

- Sessions are logged (and ideally recorded)

- Vendors have limited reach to only what they need

- Remote access terminates outside critical control zones

“Good” vendor access workflow (practical)

- Vendor requests access with ticket/change record

- Access is approved for a defined window

- Vendor connects via VPN/ZTNA with MFA

- Vendor lands on an OT DMZ remote access gateway

- Vendor RDP/SSH into the OT DMZ bastion/jump host

- Vendor accesses only specific target systems via allowlisted conduits

- Session is logged/recorded; evidence attached to ticket

- Access expires automatically; accounts reviewed periodically

Why this works in the real world

It balances:

- operational support needs (vendors can still fix things)

- security controls (tight reach, high accountability)

- incident readiness (you can reconstruct what happened)

Decision matrix: which should you deploy?

Most teams don’t need to “pick one.” They need to pick an architecture.

If you’re short on time: choose based on intent

- If you need a boundary ingress control point: build a bastion (hardened, minimal surface, strict policy).

- If you need multi-hop access into segmented networks: build a jump host (enforced hop, tightly allowlisted reach).

- If you need both (common): build a bastion jump host in a DMZ and treat it as critical infrastructure.

Decision table

| Requirement | Recommended approach |

|---|---|

| Centralize admin access and reduce direct exposure | Bastion/jump host |

| Enforce multi-hop traversal across zones | Jump host (ideally bastion-hardened) |

| Vendor access into OT | DMZ bastion/jump + strict logging + allowlisted conduits |

| Need session recording and credential vaulting | PAM + session proxy (bastion function) |

| Very small environment | Start with one hardened jump/bastion host + MFA + allowlists |

| High compliance/critical infrastructure | Separate layers: PAW + bastion + inner jump + PAM/JIT |

Minimum viable “secure” build (for most orgs)

If you can only do a few things, do these:

- Put it in the right place (boundary/DMZ or restricted management subnet)

- Require MFA + named accounts

- Restrict outbound reach to explicit targets and ports

- Centralize logs; alert on anomalies

- Remove unnecessary software; patch routinely

- Make it the standard path so people don’t bypass it

Common mistakes (and how to avoid them)

Mistake 1: Turning the jump host into a general-purpose workstation

What happens: browsers, email, random tools, file downloads—malware risk skyrockets.

Fix: keep it minimal, controlled, and dedicated to admin workflows.

Mistake 2: Allowing the jump host “access to everything”

What happens: it becomes a skeleton key; compromise equals total compromise.

Fix: allowlist destinations/ports per role and segment admin access.

Mistake 3: Shared accounts (especially for vendors)

What happens: no accountability; password reuse; easy credential theft.

Fix: named accounts + MFA + time-bound access + periodic review.

Mistake 4: No session logging or poor log retention

What happens: you can’t investigate; you can’t prove compliance.

Fix: forward logs to a central system; define retention; test visibility.

Mistake 5: Bypasses exist because the secure path is slow

What happens: shadow IT remote tools appear.

Fix: design for usability: stable hosts, right tools, documented process, quick approvals.

Mistake 6: Dual-homing shortcuts (especially in OT)

What happens: boundary controls are bypassed; segmentation collapses.

Fix: enforce conduit control through firewalls and keep roles separated.

FAQ

Is a jump host the same as a bastion host?

Sometimes in casual usage, yes. Strictly speaking, bastion describes the hardened boundary security role, while jump host describes the multi-hop access workflow. The safest designs make the jump host also function as a hardened bastion.

Should a bastion host be in a DMZ?

Often, yes—especially when it’s the entry point from less trusted networks. In OT, placing the bastion/jump host in the OT DMZ is a common best practice to broker vendor/admin access without exposing control zones directly.

Can I have more than one jump host?

Yes, and it’s common in segmented environments. You may use one bastion/jump in the boundary/DMZ and another in a management or engineering zone to limit reach and reduce blast radius.

What protocols should be allowed to and from a jump/bastion host?

As few as possible. Inbound is typically RDP or SSH (or ZTNA). Outbound should be allowlisted to only the targets and ports required for administration (RDP/SSH/HTTPS to management interfaces, etc.), with deny-by-default where feasible.

Is a privileged access workstation (PAW) the same as a jump host?

No. A PAW is a hardened admin endpoint (the admin’s device). A jump/bastion host is a controlled intermediate system. Many mature environments use both.